I want you to experiment with me for a moment. Just breathe. Breathe in the air that currently occupies your space. Breathe in the air that surrounds you, holds you, is your world in this very instance. After you’ve taken your first breath, I want you to now pause and, for the span of a few seconds, I want you to notice the flavor of the air. Is it sweet? Savory? Spicy? Is the flavor dull, sharp, simple or complex? How does the air feel as it goes from your nostrils to mouth to throat to lungs to belly? As you have fully inhaled and held that breath, I want you to now exhale, letting the air leave your chest, through your throat, mouth and nose. How does this feel? How does this taste? What lingers and fades? What remains? What feels as if it will never return to you again?

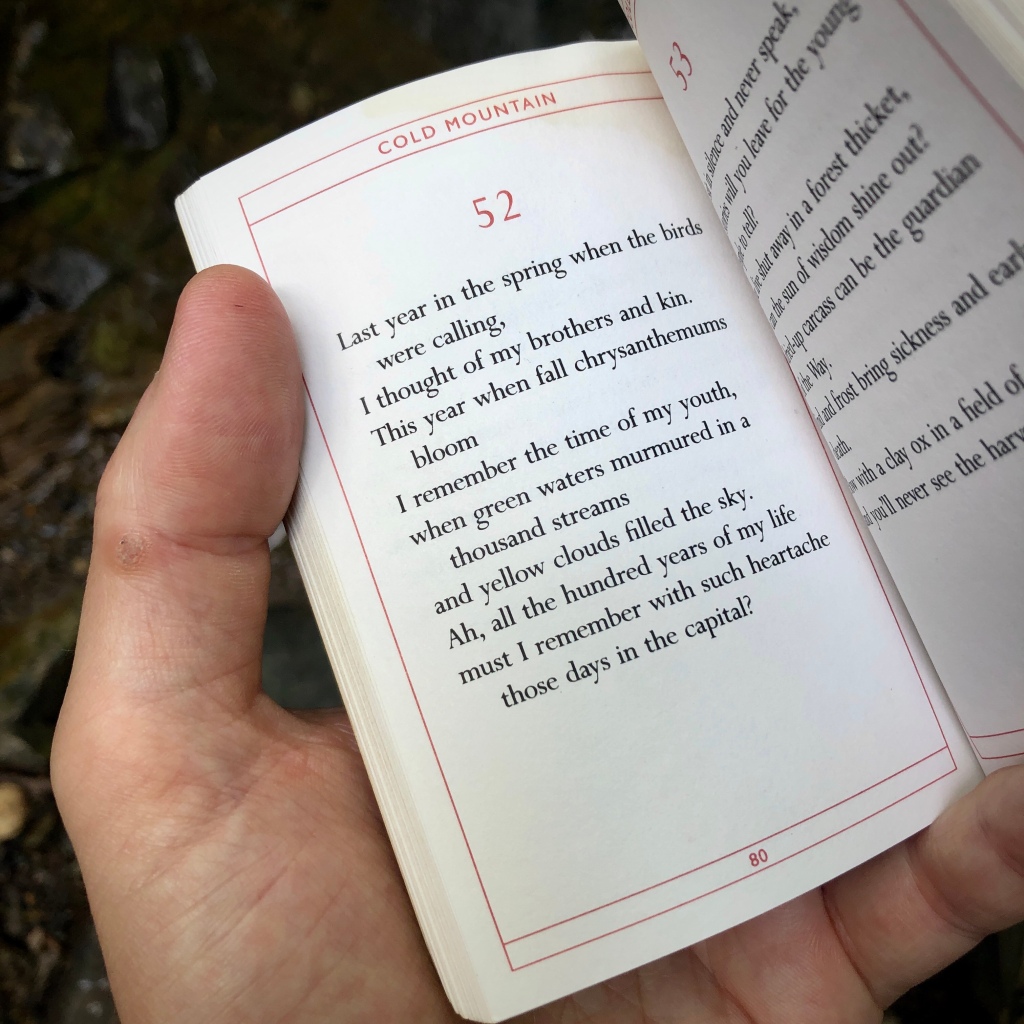

In the practice of tea, whether it’s 工夫茶 gōngfū chá, 茶の湯 chanoyu, the Korean Way of Tea, or other forms, the taste of tea is an integral part of both the experience, as well as a guide through the process of preparing tea. Over the many years that I’ve practiced the various forms of tea, the taste of tea has been a stalwart companion, pointing the way towards my learning and further delving into attaining deeper understanding of tea, as a plant, an agricultural product, an art, a cultural entity, a historical continuum. The taste of tea has taught me how to better brew a 烏龍茶 wūlóngchá, discern quality of a freshly harvested 작설 jakseol, and tell me if I’ve properly whisked a thick bowl of 濃茶 koicha. Without the taste of tea, I believed I would feel directionless, groping for something to hold onto in the dark. Yet, this is exactly what happened.

During the final days of 2023, amidst the Winter festivities and celebrations leading up to the new calendar year, my daughter and I became sick with the COVID-19 virus. So reduced was I that upon the heralding of 2024, I could barely muster the strength to write down my intentions. Soon thereafter, my wife, too, contracted the virus and, for several days, we all remained home in our shared sickbed (save for our dog, who escaped the sickness yet kept us company throughout the entire ordeal).

After our energy came back and our fevers broke, we returned to our regular routines. However, one aspect of the illness remained for me. For weeks and then past an entire month, I was unable to sense taste. For the first time in my life, for a frighteningly long period of time, I tasted nothing.

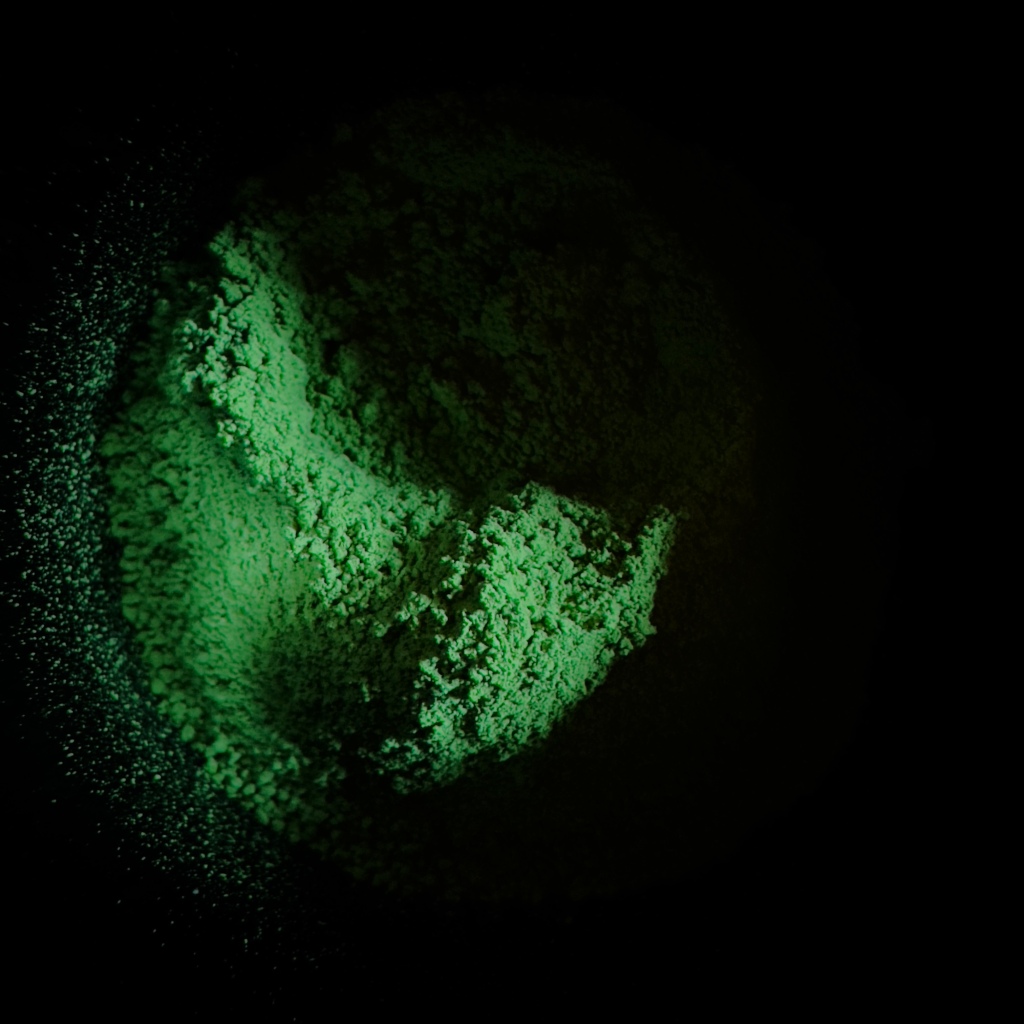

The first moments of this were oddly novel, enjoying a sense of emptiness that I’d never felt nor experienced before, ever. I’d prepare a bowl of 抹茶 matcha, one to mark the turning of the year, and taste nothing. I’d close my eyes, thinking that the momentary removal of my visual sense might help me to focus on finding what little flavor could be perceived and, still, nothing arose.

I soon began to marvel in this meditation. A sudden leap into a deep nothingness. A pure and vast abyss to explore. Nothing, so I thought, to attach one’s self to.

Alas, as the mind always does, it found a foothold.

In the emptiness emerged other clingings. The sensorial mind is one that habitually always wants to feel something and, so, it seeks anything to attach itself to, to analyze, to explore and identify. Soon each cup of tea became a means to wander through a new and unknown world, a realm of the senses, albeit one unencumbered by the sense of smell and taste.

The realization that taste, whether it was through aroma or through flavor perceived in the mouth and throat, was my primary way of understanding tea, I began to hone in on the other various avenues that now took center stage.

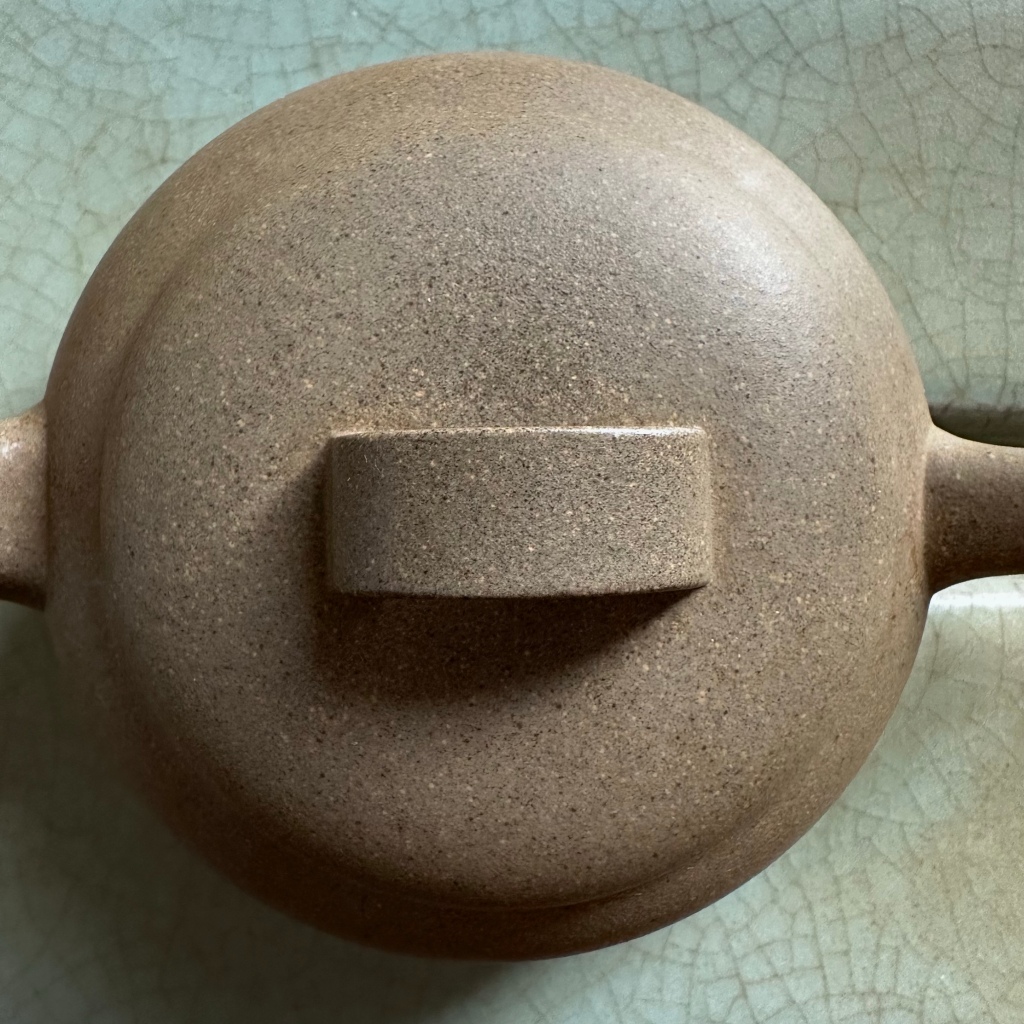

Surprisingly, touch became first of the senses I explored. During the weeks I could not taste, I recall gravitating towards a particular 宜興 Yíxìng teapot. A small 羅漢 Luóhàn (Arhat) shape teapot made of aged 朱泥 zhūní clay, made in the late 1980s/early 1990s. I had acquired it during my days as a graduate student, when I’d spend weekends escaping my studies to travel to tea houses up and down the coast of California.

In the particular instance when I found this teapot, I was in my old college town of Santa Cruz, visiting my friend April Shen’s antique store. I remember April handing me two, almost identical, teapots. Upon releasing both pots into my hands a loud thunderclap rang through the air and the electricity in her warehouse instantly shut off. Plunged into darkness, I was left to discern the qualities of both teapots without my sense of sight.

I remember how my hands felt each of the tiny vessels, first feeling their respective weight, then the texture of their exteriors, comparing both but treating each as if they were their own worlds. I could sense their volume by the shape of their bellies. I could determine how they would pour by the curve of their spouts. I felt for balance in the hand, how they would feel during use. I remember spinning and lifting the lids off of each to compare how fine the fit and crafting was. Tapping the lid against the body of the pot to determine the clay’s firing and density. Feeling the ridges and “architecture” of each of the pots to determine how structured each pot was, how the water would run off of and collect along these exterior forms, and how this would, in turn, affect the brewing of the tea.

With a sudden whir and clap, the lights turned back on and I remember looking down at each pot in the electric light, seeing them for the first time with my eyes and, yet, already knowing so much about them. I ended up getting both.

Sitting in my studio with the pot in the daylight of late Winter, I could appreciate all of the nuances I’ve come to know about this little 宜興茶壺 Yíxing cháhú (Yíxìng teapot).

As the sound of the kettle softened and water within it came to a boil, I started by warming the pot, observing the steam rise out from its dark concave. I could hear the sound of the water pushing up and around inside it, changing pitch as it slowly climbed up its interior walls.

The sound of the lid lifting off from the center of the three gathered adjoining 品茗杯 pǐn míng bēi (lit. “tea tasting cups”), and the corresponding sound of the lid setting atop the opening of the pot.

The feeling of the warmth radiating from the little teapot and then the warmth of the steam that rose from the cups as I transferred the water from the pot into them.

Emptied now, the pot awaited its next role in this play of objects.

From an antique Japanese 染め付け sometsuke blue-and-white tea jar (originally used for holding 煎茶 sencha leaves), with images of orchids rendered in blue colbalt upon its cool white surface, I drew a measure of tightly curled tea leaves.

Leaves of uniformed marbled colors of dark green, russet and red. Leaves that were harvested last Spring yet leaves I’ve grown accustomed to since I was a young boy.

Traditionally oxidized and roasted 鐵觀音烏龍茶 Tiěguānyīn (lit. “Iron Guānyīn/Avalokiteśvara/Bodhisattva of Mercy”) wūlóngchá from 安溪 Ānxī county, southern 福建 Fújiàn province, China, from the same farmer who’s made this tea now for many decades (if not for half a century).

Unable to enjoy their dry aroma, I was left to admire their visual beauty and to discern their quality on their merits of physical consistency. Lifting the old bamboo tea scoop, I readied the leaves to enter the awaiting teapot.

Using a twig I’d pulled from a fruit tree years ago, I slowly pushed the leaves into the vessel…

…working to ensure that they fell and arranged themselves…

…into a nicely formed heap within the warm clay pot.

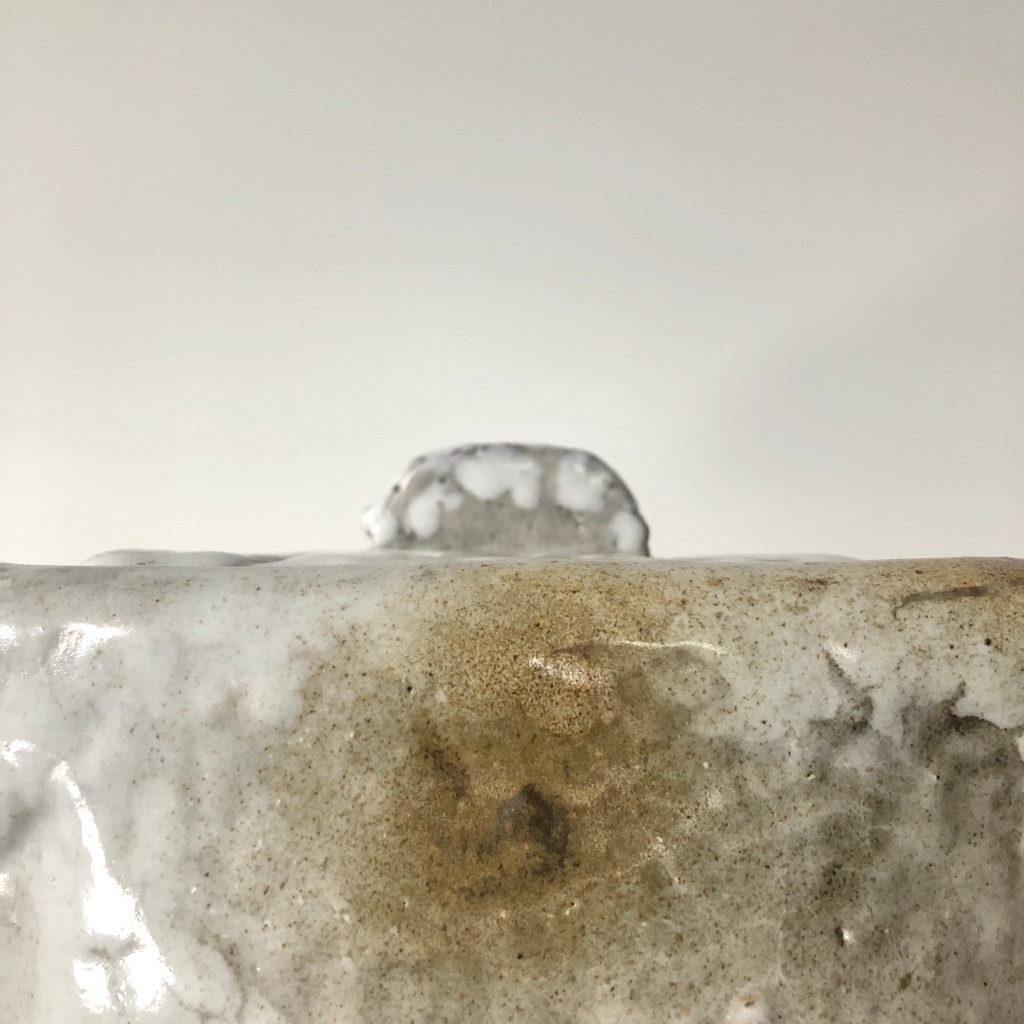

Pouring boiling water over the leaves, I took a moment to observe the first brief moments of the steeping process. Oily foam rose and collected along the circumference of the teapot’s open mouth. Steam swirled in tiny cyclones off of the surface of hot liqueur. Tea leaves lifted and tumbled and fell in what looked like a tiny choreographed dance.

Closing the teapot, I sat and waited for the meniscus bubble to travel down the spout of the teapot. I sat and waited for the teapot’s color to deepen, from a bright sanguineous red to a deep lustrous crimson.

As I waited, I cleansed and emptied the warming cups.

As I waited…

…I listened to the quiet hiss of the boiling kettle.

Pouring a tea that I could not taste was a new experience. The color starts off pale and slowly grows deeper.

From one cup to the next and back again, the tea continues to decant, further steeping as long as it remains within the pot.

By the last draught, the tea is fully steeped. The last few drops are purported to be the best, offering the sweetest and most complex flavors.

Alas, I’d taste none of these.

Looking down into the three cups, looking down at the emptied pot (save for the unfurled tea leaves it contained), I recall the sense of anticipation. Having navigated the flavorless abyss for more than a month, I’d succumbed to the possibility that this might have become my new life, as so many have already succumbed to Long COVID. I did not fear this, although I wondered how I would continue to develop my tea practice with what I felt was an insurmountable challenge.

During this time, I constantly reminded myself that the basis of gōngfū chá was to attain skills through challenging oneself, and this instance was no different. A teacher leaf. A teapot. Hot water. Warm cups. Cold air lingering in my studio. These were challenges I’ve faced and overcome before. No taste would also have to be met and new skills to address this would ultimately arise.

I remember lifting the first cup. I studied its deep amber hue, noting that it was not one uniform color but a myriad of different shades and tones. How at its center the color appeared vibrant and clear, and how it shifted along the edges, with hints of green, purple, and gold.

As I lifted the cup closer, I made an attempt to smell the aroma (as I’d done time and time before my sickness had struck). While no scent was detected, I could feel the warmth of the tea radiate and enter my nostrils, reaching into the back of my throat and soft palate.

As I took my first sip, I aerated the liqueur with an audible slurp. The smallest of sip to pull the tea back over my tongue, back to the upper reaches of my soft palate, and back to the entrance of my throat. Here, where typically I would taste tea, I could feel the heat of the liquid. Here, too, what emerged, as if from shadows, were the properties of the first steeping.

In place of the complex swirl of flavors that a traditionally oxidized and roasted Tiěguānyīn displays, I could feel the tea produce sensations across the interior of my mouth and throat. Where there would normally be an initial sweetness balanced with a mild bitterness, followed by a cascading array of floral notes ranging from marigold to honeysuckle to rose, there were textures, shifting rapidly from slick and viscous to sticky like butterscotch, astringent like pomelo rind, and dry like the tannic sensation of eating walnut skin. The palate awoke despite being unable to taste and the mouth and cheeks reciprocated with salivation. The finish was met with slight tightening of the sides of the cheeks and back of the throat, followed by a long and lingering softness, both dry and moistening, building from the first small sip to the second and finally to the completion of the first cup. As I breathed out from my throat and into my mouth, these sensations echoed and remained.

I sat for a moment in wonderment. The words that my many mentors, teachers and trainers from my past seemed to well-up inside of me. These words, classic descriptors from Chinese tea culture used to give a linguistic framework for understanding tea’s complex vocabulary of flavors and sensations, suddenly started to come back to me.

收斂性 Shōuliǎn xìng may be used to describe the astringent quality of tea when it feels akin to biting into a rind of a fruit or akin to the astringent tannins found in higher oxidized tea. Though sometimes associated with rougher teas, if the tea is well-crafted, this quality can be balanced and interplay with the sweeter flavors of the tea. Traditionally oxidized and roasted Tiěguānyīn contains a subtle tannic quality, an enjoyable boldness that waivers on bitterness. While I could not taste this, the drying, tingling, and slightly puckering sensations caused by the tannins present in the tea were very present.

生津 Shēngjīn (lit. “life haven”) refers to the aspect of tea that can quench one’s thirst through the moistening of the mouth and generation of saliva (sometimes less poetically referred to a 口水 kǒu shuǐ, “mouth water”). The sensation is pleasant, revitalizing, and nourishing. Even after the first cup’s sensations lingered in my mouth minutes after I had completed it, I could still sense this aspect of its quality. My body, despite my lingering symptoms, felt nourished, relaxed and revitalized by the tea.

回甘 Huí Gàn (lit. “return sweet”) is the first of the long lasting sensations a tea can leave in the body. It is the convergence of bitter and sweet, producing a long and complex lingering finish which is the hallmark of a high quality tea (especially oolong tea). As I finished each sip of tea from the first cup, I could feel the confluence of the drying astringency with the silkiness of the sweet meeting in the back of my throat and returning to coat my mouth. This felt as if the tea was opening to new complexity, the beginning of its expansion across my senses despite not being able to taste the tea itself.

喉韻 Hóu Yùn (lit. “throat rhyme”) is expressed when a tea has been fully consumed and leaves a pleasant, resonating sensation in the throat. The “rhyming” comes with the subtle harmonizing of the sensations in the mouth and soft palate with that of the throat. Tea connoisseurs often consider that the taste of the tea is often at its richest and most complex when reflected in the Hóu Yùn. However, as I perceived it without my abilities to taste the tea, I could still feel the slick, smooth, rich textures, and complex, long and lingering sensations it left in my throat.

體感 Tǐ Gǎn (“body sensation”/“physical perception”) started to arrive after the second cup, and only in a slightly perceptible way. Tǐ Gǎn refers to the physical experience that tea brings once it has fully entered the body, changing the way the body feels and how the tea is perceived as it moves through the body. The warming qualities of the tea liqueur can be felt as it makes its way down the throat and to the stomach. There is a slight increase in the body’s vital energy as it begins to metabolize the tea. This coincides with a cooling effect as the sweet and bitter flavors subside and refresh the mouth, throat and body.

All the flavors described in tea are caused by a kaleidoscope of different naturally occurring chemical compounds, each of which also have their own attributed sensations. Catechins, a type of tea polyphenol, causes slight pleasant grassy bitterness in tea, but also can produce a slight astringent sensation. Caffeine, which contributes to bitterness, is also drying. Caffeine is also one of the primary compounds found in tea that wakes up the body and mind. Tannins contribute to a bitter and astringent taste in tea also helps to give the tea its body and complex texture, ranging from a slight drying sensation, to sharper, more interesting tones that linger and fade. L-theanine, an amino acid which contributes to a balanced sweetness in tea, can also be perceived in the freshness of the tea and the clean texture on the palate and throat. It, like caffeine, is responsible for the slight “pick-me-up” tea produces, but also promotes a sense of bodily relaxation. Finally, carbohydrates such as fructose, sucrose, and glucose, all of which are produced by photosynthesis, contribute to the complex sweetness of tea, as well as the long returning sweetness, fading soft textures, and refreshing energy evinced in Huí Gàn, Hóu Yùn and Tǐ Gǎn.

Finishing the last of the three cups, I endeavored onward to brew the tea again.

The leaves, almost fully open from the first long steeping were covered once again in the boiling water from my kettle.

Closing the pot once more, I used the pause as an opportunity to continue to feel the tea and its energy course through my body.

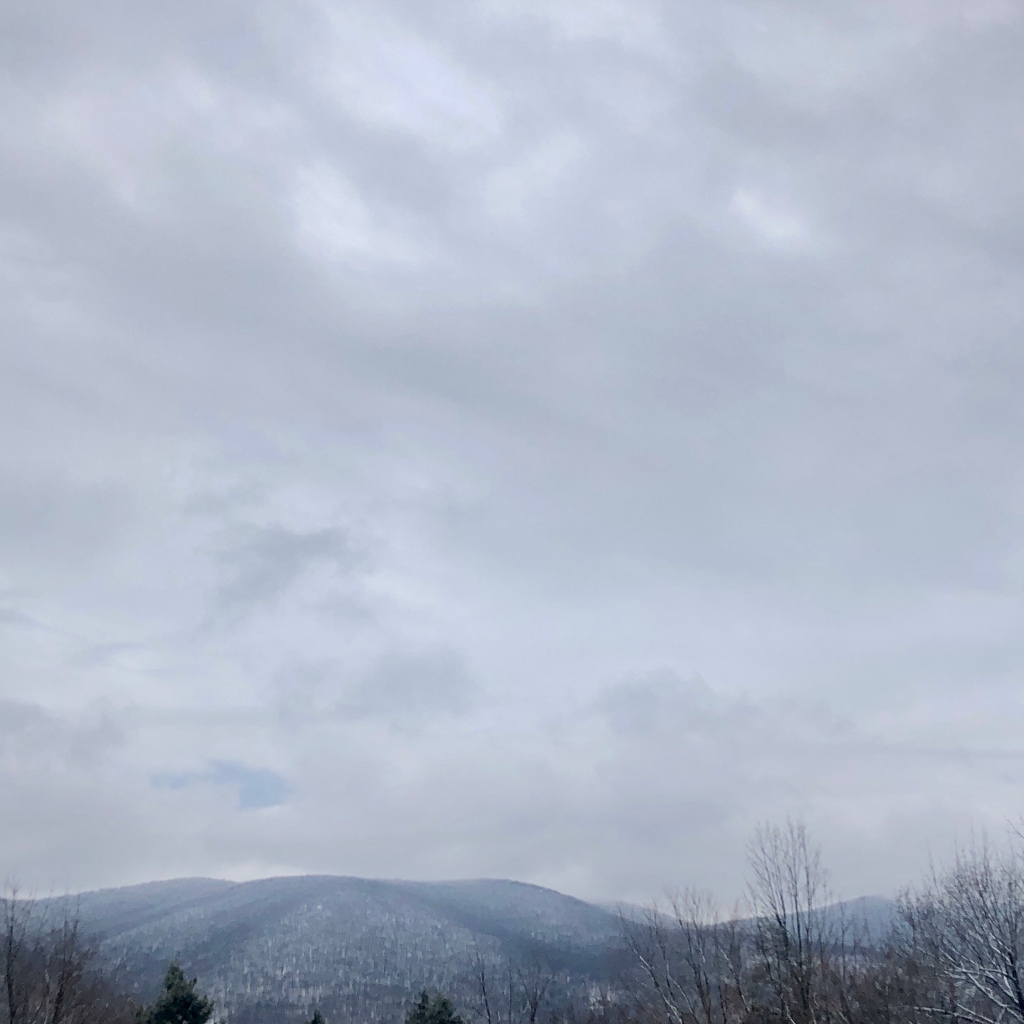

Late Winter in Upstate New York is marked by intermittent days of ice and snow. One day the mountains will look dark and bleak, the next they are set alight in a dusting of fresh snow.

Outside in my garden, snow had been piling up, creating a soft, cold world…

…where shadows cast long and blue…

…where footfalls of wild animals traced…

…where the old life of last year stood rigid and bare…

…where the sun pushed through treetops and gently sloughed off the snow by midday.

In my momentary existence of my tastelessness, I reveled in the not knowing and feeling my way back to tea. As the snow covered and concealed forms all around, so, too, did my lingering symptoms. Sipping tea as if it were medicine both for the mind and body kept me sane in a sense as I tumbled through this novel if not terrifying experience. A challenge to meet and make friends with and learn what all I could from the interaction. In conversation with my sickness and my body, the tea was telling me more than I could have ever imagined.

A second steeping and I could feel my cares drift away.

A third, and my body began to feel lighter.

A fourth and fifth…

…and the tea’s color lightened.

Six, seven, eight more steepings…

…and the tea and I kept pace.

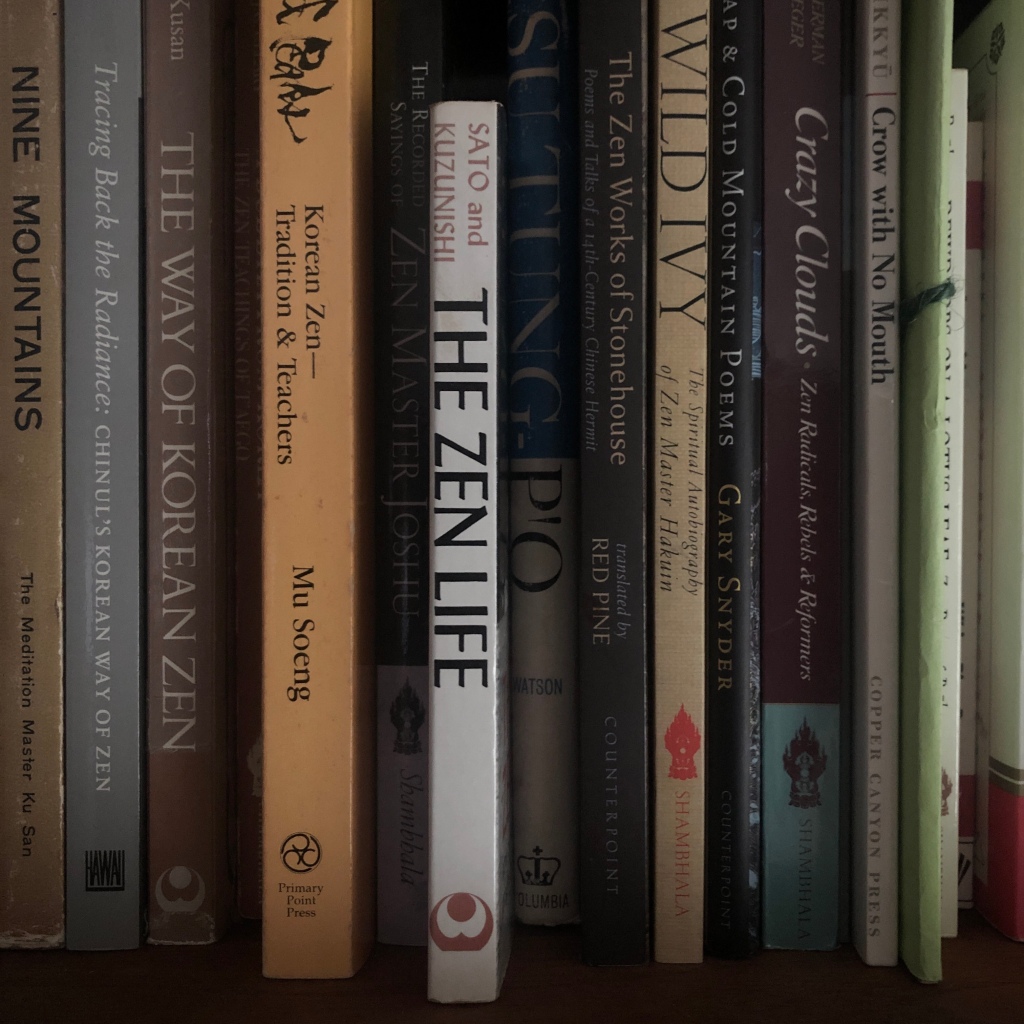

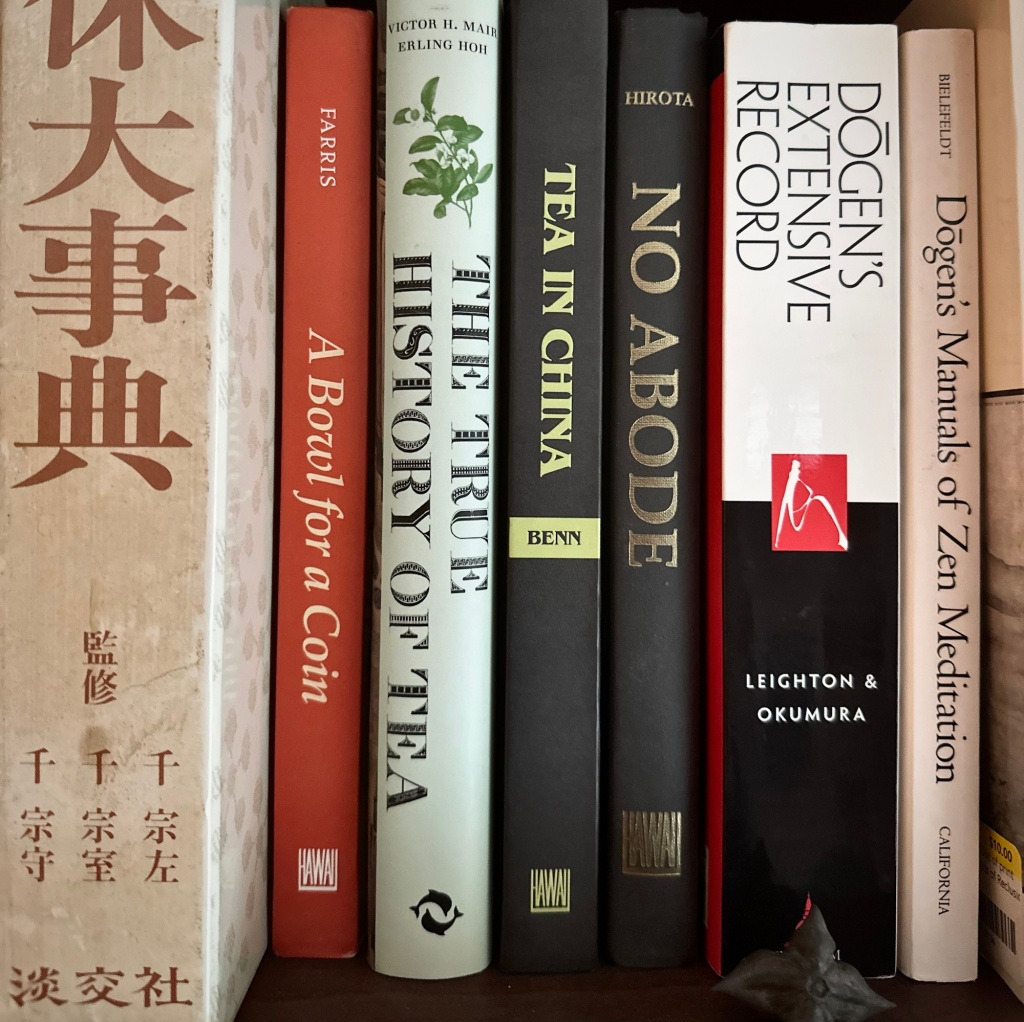

Nine and ten and I began sitting up, rambling around my studio, searching for books on my shelf, my body electrified with the energy of the tea.

Eleven and twelve and I began to spin in a light hearted joy, finding pause in my attempt to decipher the calligraphy carved onto an old bamboo tea scoop.

茶醉 Chá Zuì (lit. “tea drunk”) soon gripped me, a culmination of all of tea’s remarkable sensations into a giddy, relaxed, and settled feeling. For those who ascribe to it, the 茶氣 Chá Qì (the tea’s frequency, energy, life force, literally “breath”) was surging through me, as palpable as the myriad of sensations that continued to play across my nostrils, tongue, cheeks, soft palate, throat, stomach, chest, forehead, body, and mind.

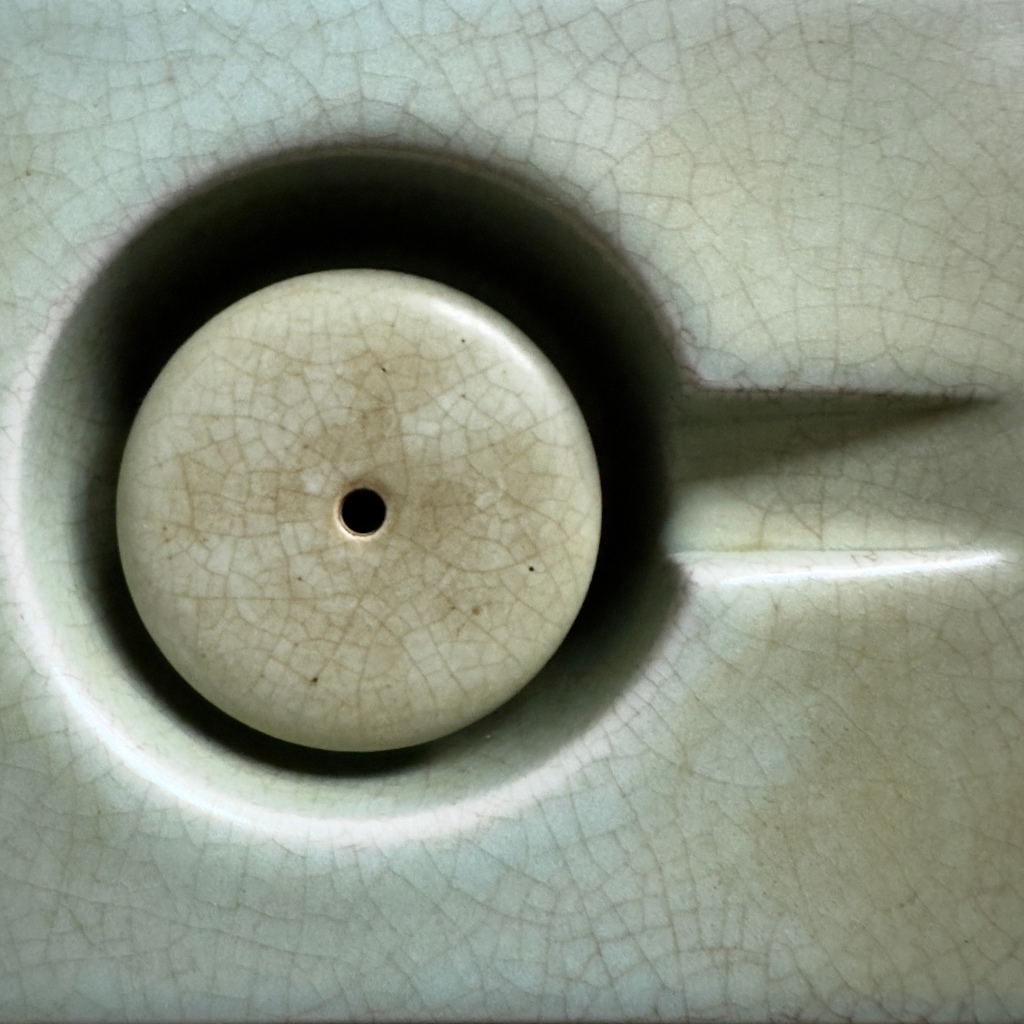

While I tasted no tea that day, as I cleaned my old 朱泥茶船 zhūní cháchuán (lit. “cinnabar mud/clay” “tea boat”), I remember looking down into its empty concave form. Slick with the cool water now evaporating from its soft skin, I could see the many layers of tea oil that had settled into it, giving it a fine patina of time and experience. Used for decades now, the brick-red of the clay shone like a jewel, even if it were just an old dish. The secondary nature I’d always ascribed to the piece seemed more artificial on this day. What I’d seen as a vessel that collected the off-pour, the overflow, the space around the teapot, now seemed more primary in its purpose. The cháchuán lifts the teapot off from the table, providing it a place to be used, clear from anything but itself and the tea it contains.

Here, too, I began to think of how the senses often take varying levels of prioritization when one 品茶 pǐnchá, the term classically used when tasting tea. However, the character 品 pǐn is comprised of three mouth (口 kǒu) radicals. In a more expansive translation of pǐn, “taste”/“tasting” can be read as “to grade” or “to judge/discern quality or character”. The three mouth radicals, too, may be linked to the multiple ways one consumes tea, not just to taste with the mouth but to see with the eyes, feel with the body and perceive with the mind. In this understanding, to taste tea is to taste it with all the senses. To see it, to savor it, to feel it beyond the flavor alone.

In the months that followed my recovery, I slowly but eventually did regain my abilities to taste tea. However, I still find myself seeking for those moments fleeting after I’ve sipped a cup, after I’ve finished a brew, when the feeling of tea is all that remains, perhaps as a reminder of this brief time in my life when it was all I had.